‘I was a child carer – it made me who I am today’

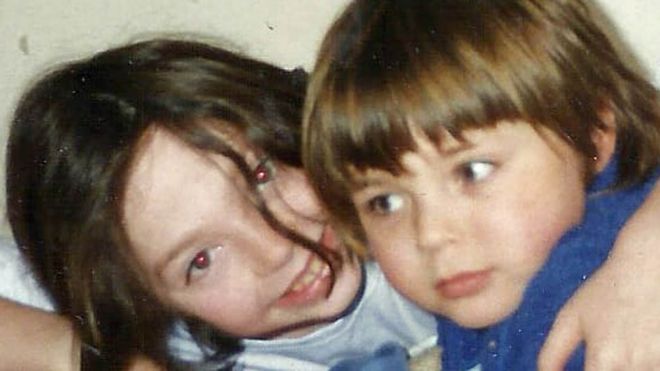

From the age of 12, writer Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett helped look after her severely autistic brother. Like hundreds of thousands of other young carers, she took on major responsibilities early – but says it made her the person she is today.

Being a young carer makes you different from your friends. This is one of the first things that you learn. You visit their houses after school and notice how different their lives are from yours. Their houses seem tidy, quiet and peaceful.

Mine was the opposite.

My younger brother is severely autistic. He was diagnosed when he was four, but we knew there were issues before then.

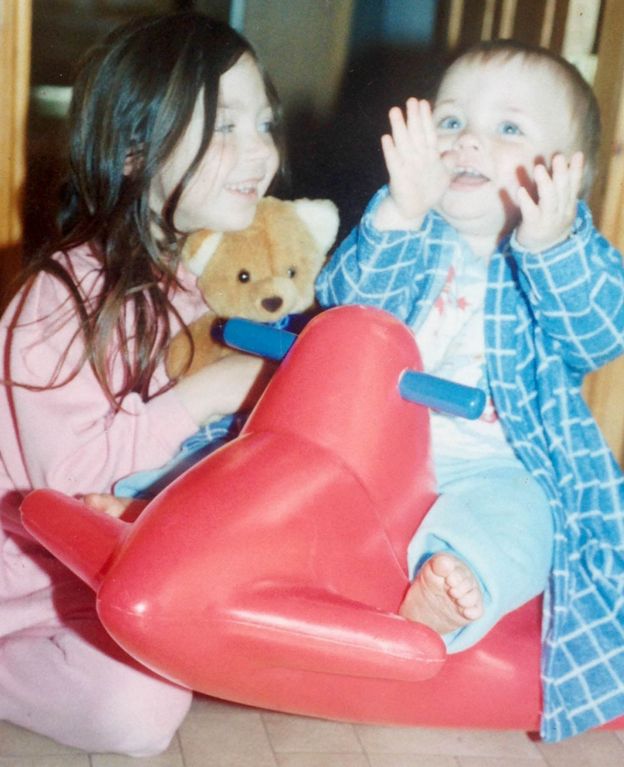

Even as a baby, he wouldn’t stay still when you tried to hold him – my mum, Anna, said he was like an octopus wriggling in her arms.

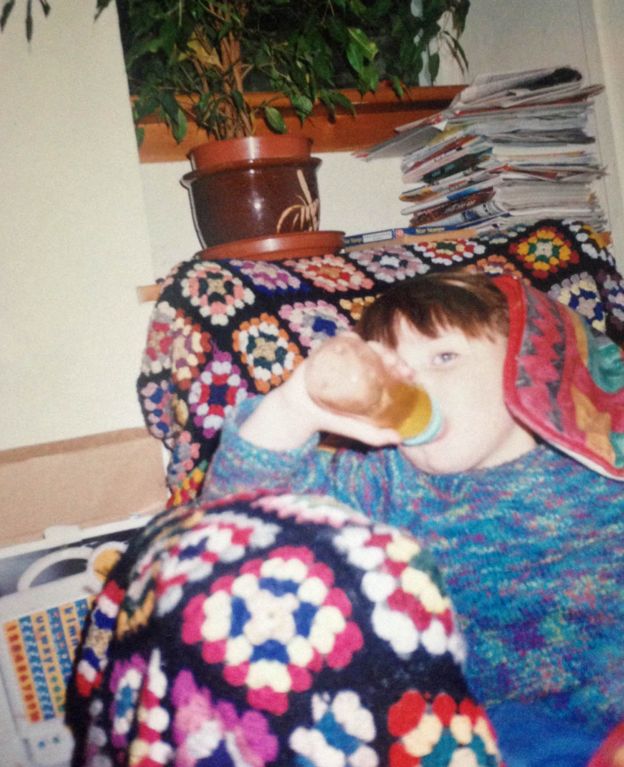

As a toddler, he was hyperactive. He tore through our house, leaving chaos in his wake. He would climb furniture and banisters, empty cereal packets and cartons of orange juice on the floor, scribble on the walls.

He didn’t sleep. He didn’t talk. We knew our lives would be changed by his autism, but we didn’t realise by how much.

I am six years older than my brother, and cared for him along with my mum until I left home in North Wales at 18 (my parents separated when I was 12).

It’s been estimated that 700,000 children and young people across the UK, some as young as five years old, are caring for family members. But the true number is likely to be much higher, as many are hidden from view.

I know what an isolating and difficult experience it can be – growing up, I had no idea there were so many other children out there in similar positions, caring for ill and disabled relatives.

When you are a carer, it can be hard to relate to your friends, with their “normal” lives.

You have responsibilities. You have to grow up very quickly. You can’t muck about and be so carefree.

I certainly didn’t misbehave – I felt that my mum, who did the lion’s share of the caring, had enough to deal with, without me being naughty as well. My brother barely slept and she was exhausted most of the time from getting up more than four times a night. I would care for him while she snatched an hour of sleep and, as I got older, for much longer stretches so that she could go to work or spend the evening with her then partner.

I did have moments where I felt quite separate from my classmates, who were still having their dinner cooked for them when I was preparing meals from scratch. On the other hand, being able to cook stood me in good stead in the long run, as did many other skills and traits I learned from being a carer – responsibility, compassion, empathy, selflessness, multi-tasking, patience and generosity.

A sense of humour was a must, especially when it came to toilet trouble. Mum and I cleared up enough poo for a lifetime (this may be why, at 31, I am still not sure how I feel about having children).

It taught me basic plumbing – give me some string and a coat-hanger and I can fix a broken toilet – but also how to laugh when you’re up the proverbial creek. You had to, because otherwise you would cry. Then again, we did lots of that too.

We had two floods and a fire, and endless weird and embarrassing moments. People loved my brother – he was a very cute child with a huge goofy smile and big blue eyes, but his behaviour was – how can I put it? – unpredictable.

Sometimes when we were out and about he would take his clothes off and run around while we chased after him, waving his trousers desperately like a flag. He was always falling into lakes and rivers, or reaching into people’s bags of chips and plucking them out.

He had no sense of fear so you had to be hyper-alert. He once ran into a field with a bull, which was terrifying. Thankfully we got him out in time.

He also had tantrums in public and people would stare and make comments. I always confronted them when this happened – being a young carer made me quite feisty. I had a keen sense of injustice from a young age and that has translated into my journalism, particularly when it comes to the hardship and discrimination that disabled people often face.

Schoolwork was difficult as sleep was disrupted, and the house was really noisy all the time.

I learned how to concentrate even if all around me was total chaos. I developed a love of reading and tore through several library books a week. In a way, being a carer is what made me a writer. When things were difficult, I needed a way to escape, and reading provided that, but it also made me interested in people.

You learn so much about humanity when you are looking after someone vulnerable and you need empathy, a vital skill when it comes to creating your own characters.

Teachers didn’t always understand. I’m not surprised that Carers Trust Wales have found that many children who are carers are not known to local authorities. Adults often don’t think to ask, or when you try to explain why your homework is late, or indeed why you are, they will just say that you are making excuses. I’ll never forget the horrible reaction of an after-school drama teacher who refused to accept that I had missed a rehearsal because I had to look after my brother.

Nevertheless, for every nasty person there were many more kind ones.

I had a couple of close friends who lived nearby – Hannah and Kate – who have always been there, and would keep me company when I was on my own with my brother at home because mum had to work or pick up a prescription. (Hannah is now a mental health nurse and says her experience looking after my brother helped inspire her to pursue that career.)

As I grew older, I opened up to more friends about my home situation. They were all really supportive, treating my situation as though it were no different from anyone else’s. Sometimes people act as though they are uncomfortable around my brother because of his strange seeming mannerisms and noises, but they never did. They helped me realise that there is no such thing as a normal family.

My mum trusted me, and in many ways that worked out quite well – as long as I made sure my brother was OK, I could have people over and she could benefit from finally having a bit of a social life. Often friends would help put him to bed, and I remember being particularly touched to find my friend Sam reading him a bedtime story.

Leaving home was hard. By that time, my brother was in a special school, staying overnight during the week and coming home at the weekends. Yet I still felt like I was abandoning my mum, who was finding it increasingly difficult to cope.

My brother had grown very big and strong and she couldn’t control him any more. He had also developed epilepsy, which needed careful management and supervision, and his obsessive-compulsive disorder meant that taking him outside was more and more difficult. She became very isolated.

I missed them both terribly, because although things had been hard at times, we were a family.

I cried for two weeks, and I think the sadness and the exhaustion are with me even now.

Although I have a good job and a happy life, there are some days where I still feel very low.

When my brother was nearly 15, things became so difficult for my mum that he went into school full-time. He is now 25 and lives in a care home. He is very happy there – his carers are brilliant, and I see him as much as I can for walks on the beach and trips out for lunch.

I am grateful for how lucky we are – not everyone receives such good government support. If the help hadn’t been there, I might never have left home. I certainly wouldn’t have gone to university or have established a career as a writer.

Whenever I meet young carers, I want to give them a hug and tell them that I know what they are going through.

They should be given more support – both practical and respite care. I certainly would have benefited from some counselling.

No child’s education should suffer because they are looking after a family member, they should be encouraged by adults, and given the help they need.

Sometimes I am asked if I wish my brother had been “normal”. It’s a strange question, because it’s essentially asking me if I wish he were a different person.

Obviously, I wish that he did not have to suffer, which he does as a result of his epilepsy and anxiety. But I love my brother for who he is, and looking after him has been the defining experience of my life.

Caring has made me strong as well as sensitive. It has made me a kinder person and given me the motivation to fight for social justice. But most of all I feel lucky to have felt such profound, unconditional love for my little brother. That has been a gift.